|

| Patrick Stewart and Alec Guiness in Smiley's People |

When I first encountered Lidda the Rogue in the 3rd edition Dungeons and Dragons manual, I didn't run into a lot of fantasy that really suited me. That was probably my fault as much as the genre's, but there was a level of complexity and intrigue that I didn't see back then. I should probably have been looking harder.

I encountered the feeling I wanted to create more

often outside fantasy than in it. I found it in noir: in the books of

James M. Cain and early James Ellroy and above all, in the novels of

Raymond Chandler, who I think is one of the best

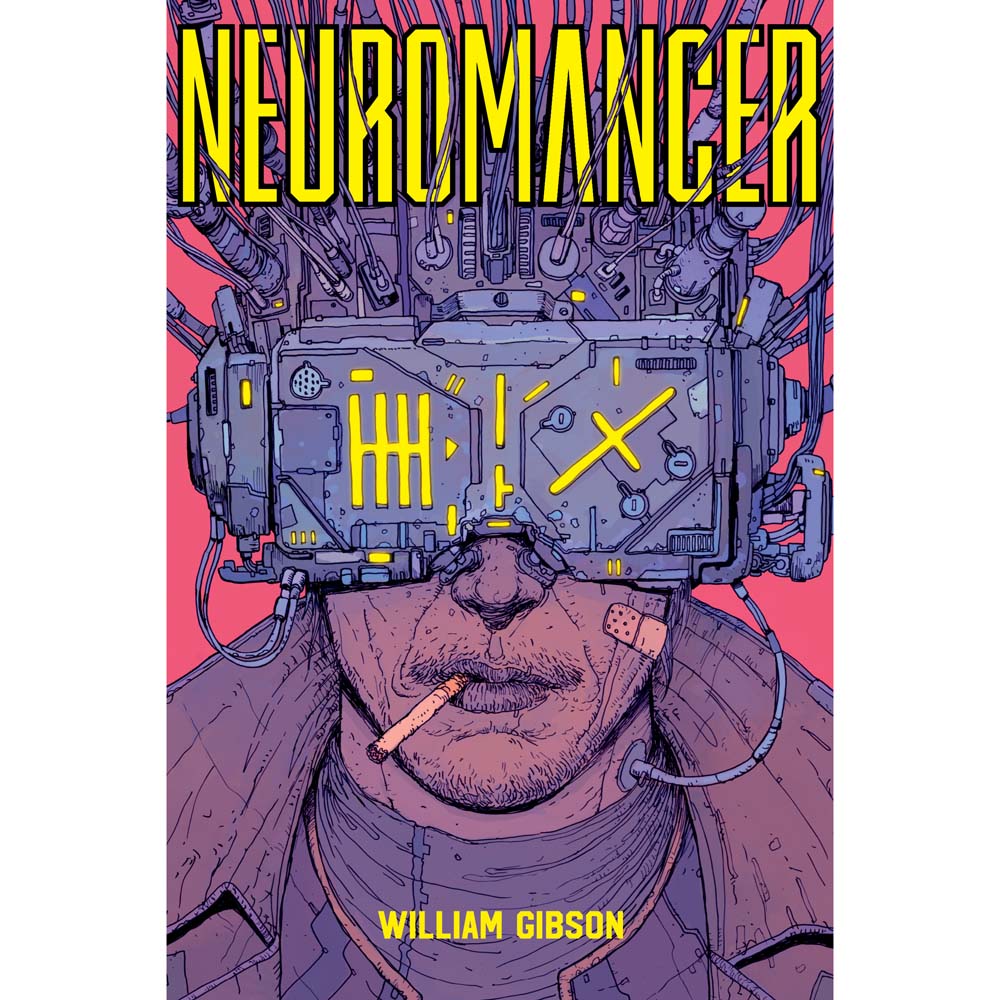

writers of the 20th century. I also found it in William

Gibson’s Sprawl trilogy, which defined the subgenre of

cyberpunk in science fiction, and the murky, downbeat spy novels of John le Carre. All of

these books contain violence, corruption and subterfuge,

but there’s more to them than just chaos and death. All of them involve flawed characters trying to make the best of their position: whether by solving a mystery, hacking a company computer system, or

unmasking a spy, using whatever cunning and improvised

gear they can find.

|

| Cover art by Josan Gonsalez. Note the obligatory cigarette! |

And they all involve a sense of morality. Richard Morgan (of Altered Carbon fame) recently observed that all good noir involves not just noticing that the status quo is bad, but fighting against it. Raymond Chandler's detective Philip

Marlowe struggles to find justice in the corruption of 1940s Los Angeles. George

Smiley might fight dirty, but he’s most certainly on the right side of

the Cold War. Even in the weird dystopia of

Gibson’s world, there are real monsters to be defeated. That sense of

justice seems to be to be one of the most basic human emotions. As Chandler himself put it in "The Simple Art of Murder": "Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean".

| Bit of a fantasy title, come to think of it |

I think without this sense of morality - even a skewed morality that is as much about revenge as justice - it's easy to produce a kind of war-porn, where the story exists for little more than shock value. Or, just as bad, you end up telling stories whose morals are too simple: yes, war is hell, but that's nothing new. As another author - in fact, one who'd written several Warhammer 40,000 novels - once told me, darkness works best when there's light for it to contrast with, and vice versa.

As such, I think it is in the tradition of noir, as I understand it. A single determined person looks for revenge in a corrupt city and, in doing so, uncovers a conspiracy. And that search takes them to some very dangerous places.